Textile Item Number: Af489 from the MOA: University of British Columbia

Description

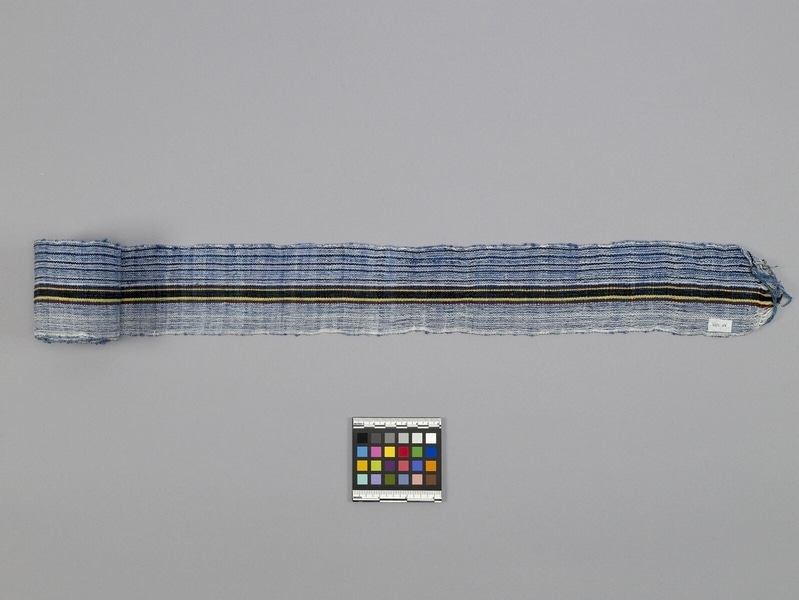

Textile composed of a long and narrow strip of woven cotton with an indigo horizontal weft. The warp has a stripes of varying width of different shades of blue. An indigo stripe flanked on both sides by thin yellow and red stripes runs lengthwise along the centre. One side is not tightly woven, and the ends are unfinished.

History Of Use

Strip of woven aso-oke. The strips are usually sewn together with similar pieces to make garments and other wearable textiles. West African narrow strip weaving appears to go back to the 10th century. The tradition may have originated in North Africa, or western Asia, but no definitive evidence has been found. Strips are made by men, typically in 8 to 15 cm widths, on a variety of loom types. They are sewn together to make material used for garments and other fabric products. Aso-oke was used for everyday use, and traditional and religious occasions. The garments made were sokoto (trousers), buba (top or blouse), agbada (robe), fila (cap), iro (wrapper), ipele or iborun (shawl), and gele (head tie). Generally, aso-oke is classified into three main types: etu, alaari, and sanyan. They are identified by their pattern- achieved through extra weft brocading technique- and colour, as well as their use for designated traditional ceremonies. Aso-oke is usually worn in collective groups, in which case it is referred to as aso-ebi, which refers to cloth worn by well-wishers such as friends and family for a particular celebration. Aso-oke use was impacted by British colonization as economic policies implemented then favored the influx of foreign goods, especially British cotton manufactured goods at the expense of indigenous traditional textiles industries. Mass-produced English-style cotton garments, and the introduction of foreign yarn, competed with hand crafted aso-oke leading to decline in patronage and production, evident by the early 1900s. The introduction of Islam and Christianity to Yorubaland also introduced new dress styles for converts, affecting the popularity of aso-oke. British garments were largely seen as markers of prestige, innovation and civility over indigenous clothing. However, the struggle for independence leading up to 1960 ushered in a wave of cultural nationalism, leading major ethnic groups to dress in garments particular to their region. Aso-oke can be found in markets today and is still worn at special occasions, such as weddings, birthdays and burial ceremonies around the world.

Iconographic Meaning

This particular strip is considered a variation of the etu type of aso-oke. Etu (“fowl”) is known by its dark blue colouring with light blue stripes. It is supposed to resemble guinea fowls feathers and is used as a social attire for chiefs and elders among the Yoruba. The small checks of light blue on dark indigo are called petuje (junior etu). In general, Aso-oke is also known to symbolize protection, especially from spiritual problems. It is used as a sacred cloth by a cult called the Ogboni society, as a covering for religious objects, and is said to be prescribed by traditional priests as a choice of attire for wedding ceremonies to guarantee the success of a marriage.

Item History

- Made in Ibadan, Nigeria

- Collected during 1957

- Owned by Albert C. Cooke before November 2, 1978

- Received from Albert C. Cooke (Donor) on November 2, 1978

What

- Name

- Textile

- Identification Number

- Af489

- Type of Item

- textile

- Material

- cotton fibre, dye and indigo dye

- Manufacturing Technique

- woven and sewn

- Overall

- height 8.4 cm, width 338.0 cm

Who

- Culture

- West African

- Previous Owner

- Albert C. Cooke

- Received from

- Albert C. Cooke (Donor)

Where

- Holding Institution

- MOA: University of British Columbia

- Made in

- Ibadan, Nigeria

When

- Collection Date

- during 1957

- Ownership Date

- before November 2, 1978

- Acquisition Date

- on November 2, 1978

Other

- Item Classes

- textiles

- Condition

- fair

- Accession Number

- 0495/0005